Abstract: A national healthcare company applied the Malcolm Baldrige Criteria for Performance Excellence and its “Are We Making Progress?” survey as an annual organizational self assessment to identify areas for improvement. For 6 years, Liberty Healthcare Corporation reviewed the survey results on an annual basis to analyze positive and negative trends, monitor company progress toward targeted goals and develop new initiatives to address emerging areas for improvement. As such, the survey provided a simple and inexpensive methodology to gain useful information from employees at all levels and from multiple service sites and business sectors. In particular, it provided a valuable framework for assessing and improving the employees’ commitment to the company’s mission and values, high standards and ethics, quality of work, and customer satisfaction. The methodology also helped the company to incorporate the philosophy and principles of continuous quality improvement in a unified fashion. Corporate and local leadership used the same measure to evaluate the performance of individual programs relative to each other, to the company as a whole, and to the “best practices” standard of highly successful companies that received the Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award.

The Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award (MBNQA) was established by Congress in 1987 to improve the competitiveness of American organizations. The Award was named for Malcolm Baldrige, who served as Secretary of Commerce from 1981 until his death in 1987. His managerial excellence contributed to long-term improvement in the efficiency and effectiveness of government operations. In 1999, the award was extended to the area of healthcare. In 2002, the Vice President of Quality Performance/Quality Improvement for a for-profit company named Liberty Healthcare Corporation (Liberty) introduced the principles of the MBNQA to its executive leadership as a promising framework for assessing and improving its organizational performance. This initiative led to a consultation visit from a representative of the Baldrige Performance Excellence Program, who recommended using their “Are We Making Progress?” (AWMP) survey as an organizational self-assessment tool. Based on years of testing and development by the Baldrige Performance Excellence Program (2011), the AWMP survey had established reliability and validity as a meaningful measure of quality. The Baldrige Program representative also allowed Liberty to utilize the AWMP survey data from the 2002 MBNQA recipients as a benchmark for comparison. Given that Baldrige Award recipients are among the most successful companies in the world, their benchmark scores could serve as a “best practices” standard of excellence for comparing Liberty’s own performance. The Baldrige Criteria for Performance Excellence were congruent with Liberty’s mission and core values, which encompass the belief that its clinicians and employees are its most valued resource and they should play a crucial role in making organizational improvements. Liberty had been providing healthcare professionals and services across the country for 20 years and its mission was “to provide healthcare management solutions of the highest quality in both the public and private sectors that are consumer-focused, cost-effective, gainful, and outcomes-oriented”. Liberty has been certified by the Joint Commission in Healthcare Staffing Services (HCSS) since 2006. By applying an established self-assessment tool that had already been validated by the federal National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), Liberty could avert the cost and delay of developing and testing its own customized tool and could immediately move forward with its desired quality improvement initiative. The company could not find any other free survey tools in 2001 that both offered this much rigor and reliability and could be applied equally well to Liberty’s private sector and public sector business lines.

The inherent flexibility of the Baldrige Criteria for Performance Excellence and the AWMP survey itself was especially advantageous to Liberty as it began its quality initiative. The Baldrige Criteria are intended as a framework that organizations can flexibly use to structure their own pursuit of quality (Borawski & Brennan, 2008; DeJong, 2009). There is no standard or suggested methodology for administering the AWMP survey or analyzing the results obtained. It was designed to be flexible and fit the needs of all sectors, including manufacturing, services, small businesses, education, healthcare, government, and nonprofits (Humble & Peterson, 2008, March). The NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), 2008) explicitly allows organizations such as Liberty to use the survey and data in whatever way is most useful or informative for the company. It is notable, however, that Columbo, Perla, Carifio, Bernhardt, and Slayton (2010) recently presented a more standardized methodology for using the AWMP surveys in a hospital healthcare setting. Similarly, Humble and Peterson (2008, March) administered AWMP surveys to 134 Phoenix-area companies to establish a baseline for organizations to use to compare their progress in implementing QM programs.

Methodology

Subjects

The subjects in the study were physicians, clinicians, healthcare managers, paraprofessional health aides, and employees at all levels of Liberty Healthcare Corporation, who were working at over 30 discrete healthcare service sites across the country. The settings included psychiatric hospitals, intermediate care facilities (ICFs), outpatient medical clinics, specialized secure treatment facilities, and other health service settings. The number of staff at each service location ranged from 2 to 5 staff at 13 sites, 5 to 20 staff at 11 sites, and 24 to 221 staff at 10 sites. Out of a total of 940 questionnaires sent out in the first year of the study, 266 responded for a response rate of 28%. Over the course of 6 consecutive years, the total number of employees declined by half, but the overall response rate steadily improved to 53% by 2008.

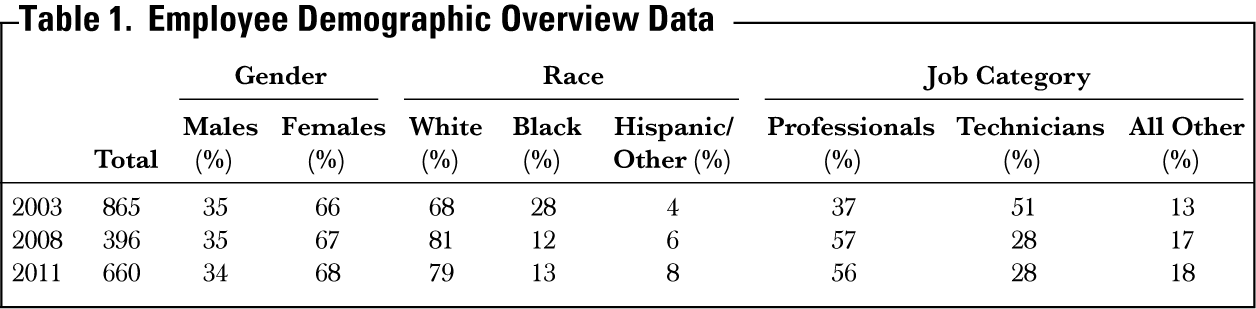

Table 1 shows the breakdown of employees by gender, race, and primary job categories based on the annual equal opportunity employer (EOE) statistics for the years of the study (2003 and 2008) and currently (2011).

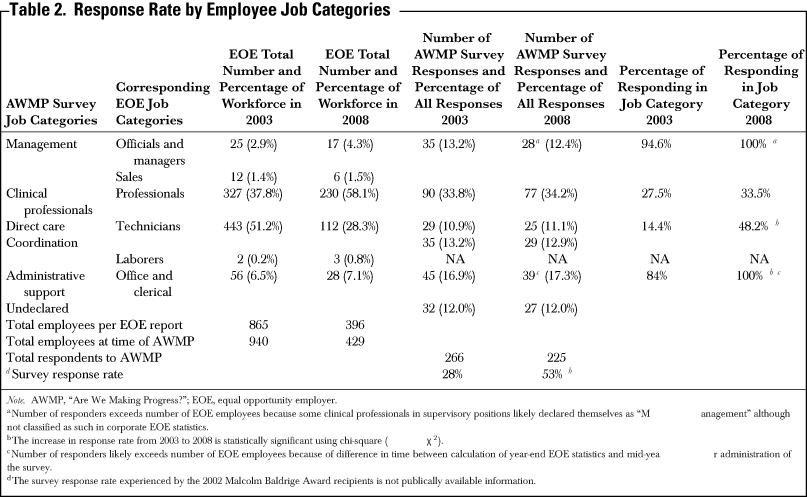

The identities of the respondents were entirely confidential, but the AWMP questionnaires were coded to identify the program location/type and respondents were asked to identify their general job category from the following list of six categories (see Table 2).

Management—This included program directors, clinical directors, senior supervisors, corporate officers and executives, and sales personnel (same as EOE category of “Officials and Managers”).

Professionals—These included physicians, psychologists, nurses, occupational therapists, physical therapists, social workers, and other types of clinical professionals (same as EOE category of “Professionals”).

Direct care—This included paraprofessional employees such as treatment aides, psychiatric techs, and residential aides, typically working in facility settings (same as EOE category “Technicians”).

Coordination—This included healthcare related case managers typically working in community and outpatient settings (also same as EOE category of “Technicians”).

Administrative support—This included secretaries, clerks, administrative aides and various office personnel (e.g., payroll, accounting, recruiters, etc.; same as EOE category of “Office and Clerical”).

Undeclared—This consisted of responders who did not identify their occupational type.

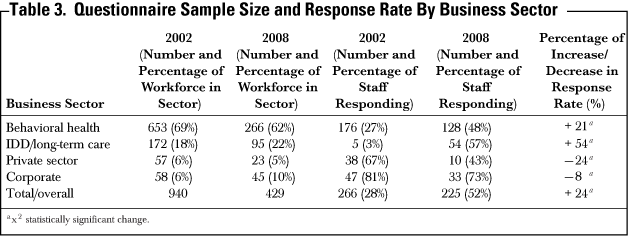

As noted, the questionnaires were also coded to identify the service site/location of the respondent, which in turn, would identify one of three primary business sectors (see Table 3).

Behavioral health—This included programs serving public sector clients with mental health and/or substance abuse disorders.

Intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) and long-term care—This included programs serving public sector clients with intellectual and developmental disabilities and/or elderly and residents in long-term care facilities.

Private sector—This included outpatient health clinic programs serving the employees of private sector companies.

Corporate—This included employees working at the corporate office headquarters.

Measure

The AWMP questionnaire consisted of 40 questions on a 5-point scale ranging from strongly agree, agree, neither agree nor disagree, disagree, and strongly disagree (NIST, 2008). The questions were presented in a sequence of seven categories: leadership (seven items), strategic planning (three items), customer focus (five items), measurement, analysis, and knowledge management (six items), workforce focus (six items), operations focus (four items), and business results (nine items).

The AWMP was reprinted exactly as designed by the Baldrige Program but with one notable modification. Liberty added one open-ended question at the end of the survey that invited staff to “give more information about any of your responses. Please include the number of the statement (e.g., 2a or 7d) you are discussing”.

Procedure

Copies of the AWMP questionnaires were distributed to every employee at each service site/location across the country with written assurances of confidentiality and a deadline date for completing and returning the questionnaires to a designated corporate officer. A return address envelope was provided so that each survey could be individually mailed back. For the larger sized program sites, the program director could gather employees in large groups, where the questionnaires would be distributed and completed and then placed in an aggregate self-addressed stamped envelope. If an employee declined to complete the survey, there was a section to record reasons why they did not wish to participate.

The Vice President of Quality Improvement/Quality Performance was responsible for aggregating the survey data from all sites and respondents, tallying the results and reporting the outcomes to the corporate officers and respective program/site directors. This annual summary report would present results for the overall company and specific program sites and divisions.

Analysis

Liberty used the methodology of the Shewhart/ Deming Improvement Circle of Plan, Do, Check, Study, Act (Deming, 1986; Shewhart, 1939) to process the results of each annual survey over the 6-year period. Each year, managers and staff would meet at both the local and corporate levels to review and discuss the AWMP survey results. Ideally, this process would conclude with the creation of strategic action plans to address areas of concern, both at the local program site and for the company as a whole.

Some of the company-wide action steps generated through this process included attainment of certification from Joint Commission in HCSS, increased training funds, suggestion boxes, monthly staff meetings for updating current information, company newsletters, customer service training, and new policies and procedures. At the same time, individual program directors were encouraged to meet with groups of their own staff to review the AWMP survey results for their site and promote dialogue with staff about Liberty and its quality improvement initiatives. Action steps were created at the individual program level based on the results and comments received.

Results

Response Rates by Occupational Category

Table 2 summarizes the total number of questionnaires distributed in the first and last years of the study and the number and percentage of respondents within each occupational category. As might be expected for a healthcare company, the largest category was clinical professionals, who accounted for one-third of the responses received. The number of responses from the other occupational groupings (and for those who did not identify their occupational group) ranged from 12% to 17% and was roughly equivalent in size. As such, the responses received each year by Liberty were considered a representative sampling. All job categories showed an increase in response rates from 2002 to 2008, but statistically significant increases were observed for the nonprofessional administrative support (χ2(1,N=555)=60.89, p < .001) and direct care/technician categories (χ2(1, N = 84) = 6.33, p < .01) as well as for the company as a whole (χ2(1, N = 1,369) = 74.69, p < .001). (Note. Given the survey anonymity factor, the “official” EOE numbers for Liberty Healthcare are presented to show the percentage breakdown by job type. However, the number of employees receiving and responding to the AWMP survey at the time of administration varies slightly from the year-end EOE numbers).

Response Rates by Business Sector

Responses were also tabulated by the three primary business sectors or “divisions” of the company. The behavioral health division was the largest, comprising about two-thirds of the total workforce. This comprised staff working in psychiatric hospitals, secure and nonsecure forensic-related treatment facilities, correctional behavioral health treatment programs, and community reentry programs. The second largest division was IDD/long-term care with roughly 20% of the workforce. This comprised staff working in state intermediate care facilities/mental retardation (ICFs/MR) and long-term care facilities for elderly and disabled.

The private sector division accounted for 6% of the respondents and comprised physicians, nurses, and staff in company clinics and occupational health programs. Finally, the employees at Liberty’s corporate headquarters accounted for 6% of the respondents. Although the proportionate size of the business sectors remained relatively constant during the 6 years of the study, the response rates among sectors in the last year of the study varied from the time of the first administration of the AWMP questionnaire. The survey response rates showed statistically significant increases in the behavioral health (χ2(1, N = 919) = 38.26, p < .001) and IDD/long-term care sectors (χ2(1, N = 267) =103.42, p < .001), but decreases in the private sector and corporate office. As Liberty became increasingly committed to this quality improvement measure, the overall response rates improved from 28% in the first year to 52% in the final year, which was statistically significant (χ2(1, N = 1,369) = 74.69, p < .001).

Response Rates by Program/Site Size

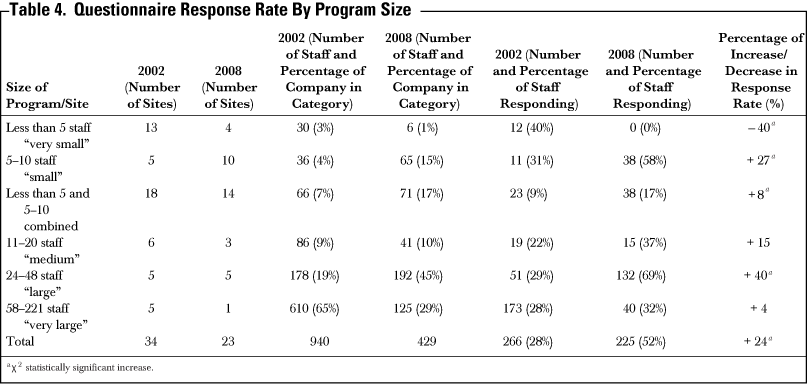

The survey results were also tabulated in terms of the size of the various programs and service sites across the country. As shown in Table 4, service sites ranged in size from “very small” (less than five staff) and “medium” (11– 20 staff) up “very large” (over 50 staff). For example, the very large programs consisted of free-standing facility operations in which Liberty employed the entire workforce, such as a free-standing 52-bed behavioral health facility, 550-bed secure forensic facility, and 220-bed ICF/MR. The medium programs typically consisted of the leadership of a “department” within a healthcare facility, such as a medical director, physicians, nurses, and rehabilitative professionals. The program directors of the medium and large programs were also given a summary of the response results for their individual service sites. Finally, the “very small” and “small” programs typically consisted of a couple of physicians at a hospital or one to three occupational, physical and/or speech therapists at a long-term care facility.

At the time of the first administration of the AWMP questionnaire, 19% of Liberty’s workforce worked in 5 “large” program sites with 24–48 personnel and 65% were concentrated in 5 “very large” program sites with over 50 personnel each. The remaining 16% worked in 24 smaller work settings with anywhere from 2 to 20 staff. As the number of very large sites reduced from 5 to 1 over the 6 years, the percentage of the total company workforce reduced from 65% to 29% in “very large” program sites and increased from 19% to 45% for “large” program sites. The number of “very small” sites shrank from 13 to 4, while the number of “small” sites doubled from 5 to 10, but the combined percentage of the total workforce in the medium, small and very small sites remained constant at 16%.

Process Management and Business Results

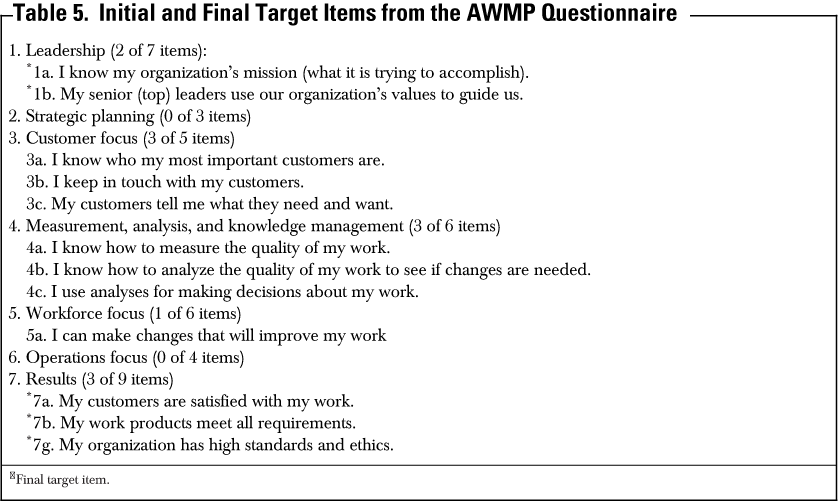

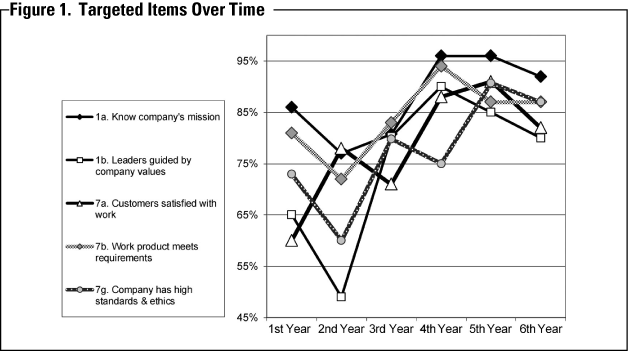

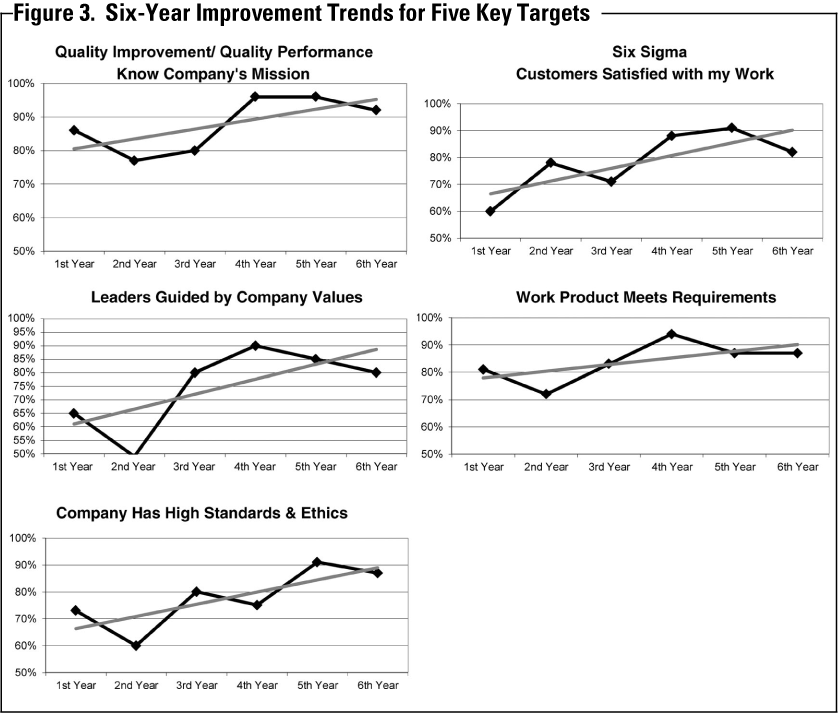

Based on the results of the AWMP survey during the first 2 years of the initiative, the executive leadership of the company decided to focus on specific issues or areas within the seven critical aspects of management of the Baldrige Criteria for Performance Excellence, which were deemed most vital to Liberty’s goals. Liberty’s leadership initially identified and targeted 12 of the 40 questions for improvement. Progress (or lack of progress) was monitored from year to year in response to various interventions, such as customer service training, employee education, and policy and system changes. Ultimately, the initial target list of twelve items was refined to focus on five key performance areas marked with an asterisk in Table 5. As shown in Figures 1 and 3, a notable drop in four target scores in the second year drew attention to the critical importance of mission (1a), values (1b), ethical standards (7g) and quality of work product (7b), and contributed strongly to the decision to make these key targets for improvement. As shown in Figures 1 and 3, Liberty generally achieved steady improvements in all five key target areas from years 3–6. In fact, there were statistically significant improvements in scores for four key items (p < .05) and near significance for the fifth (p < .06).

Despite a downward trend in year 6 for four of the five targets, it was not statistically significant and was regarded as a natural “regression toward the mean” from the very highest scores achieved in the preceding 2 years. (Note: For each survey item, the total number of “strongly agree” and “agree” responses were divided by the total number of all responses to calculate a percentage of employee endorsement of that item.)

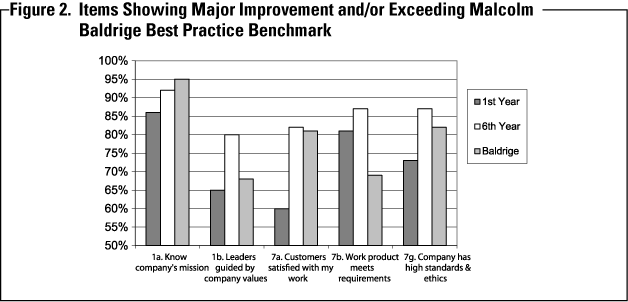

With regard to the Baldrige “Leadership” criteria, Liberty desired that all employees should be clear and unified around the company mission (item 1a) and that its business operations should be grounded in and guided by its core values (item 1b). [Note: The benchmark comparison value for each survey item was the average score of all MBNQA recipients from all industries (including healthcare) for the year 2002 as provided by the Baldrige Program. See Figure 2.] In the first year, 86% of the employees knew the company mission and 65% were aware of the company’s values and/or believed that the company was guided by those values.

Six years later, 92% of the employees knew Liberty’s mission, which was a statistically significant increase (χ2(1, N = 491) = 4.28, p < .05) and just 3% less than the MBNQA “best practices” benchmark. More dramatically, after 6 years, 80% of the employees affirmed that Liberty was guided by its core values, which was also statistically significant (χ2(1, N = 491) = 13.51, p < .001) and 12% higher than the MBNQA benchmark.

Liberty Healthcare also showed large gains in the three items pertaining to the Baldrige “Business Results” criteria. In the first year, 81% of employees believed their work met quality requirements (item 7b), but only 60% believed that their customers were satisfied with their work (item 7a). Six years later, 87% felt that their work met quality standards, which approached statistical significance (χ2(1, N = 491) = 3.53, p < .06) and was 18% higher than the MBNQA “best practices” benchmark, while 82% affirmed that their customers were satisfied, which was a statistically significant increase (χ2(1, N = 491) = 28.42, p < .001) and 1% higher than the MBNQA benchmark.

Finally, Liberty’s leadership concurred that maintaining the highest standards and ethics was a fundamental value of the company (item 7g). Dissatisfied with an initial score of 73% in the first year, Liberty implemented a new and rigorous Corporate Compliance Program. Six years later, 87% of employees affirmed that Liberty had high standards and ethics, which was statistically significant (χ2(1, N = 491) = 15.00, p<.001) and 5% higher than the Baldrige “best practices” benchmark.

Discussion and Conclusion

In retrospect, the decision by Liberty Healthcare to adopt the Baldrige Criteria for Performance Excellence and use the AWMP survey as a method of organizational self-assessment and improvement proved highly beneficial in six major ways.

Flexible, ready-to-use, economical and comprehensive measure: The AWMP questionnaire had many advantages in terms of utility and cost effectiveness. First, as a company with nearly a thousand employees who were spread across the country in 34 different service locations in 2002, the AWMP provided an easy and economical measure of performance that could be uniformly and meaningfully applied to all Liberty sites, to all three of its healthcare divisions, and to public and private sectors alike. The use of the AWMP as a performance measure also avoided the time and expense of developing and testing a new survey. Liberty could immediately adopt a well-validated tool that enabled its leadership to compare its performance to some of the most successful companies in the world with regard to seven critical aspects of management, including leadership, strategic planning, customer satisfaction, information, personnel, operations, and business results. Moreover, the AWMP tool provided the flexibility to identify, prioritize, and selectively focus on specific areas for improvement.

AWMP helped facilitate a company transformation to CQI: The implementation of the AWMP served as a means to the end of implementing continuous quality improvement (CQI) programing at Liberty. When the AWMP initiative began, the corporate leadership was not familiar with the principles and benefits of CQI or the Malcolm Baldrige Criteria for Performance Excellence.

Despite Liberty’s traditional emphasis on hiring excellent clinicians and providing the highest quality health services, it had been weak in actually measuring and demonstrating its excellence with reliable data. By assessing employee perceptions, the AWMP helped to educate and activate thinking throughout the company about the importance of measuring performance and quality in multiple domains, including effectiveness, efficiency, customer satisfaction, access to care, and risk reduction.

Thus, the AWMP initiated concerted efforts to implement and enhance customized CQI programing at many program sites, while itself becoming a common-measure that could be uniformly applied to all programs and incorporated into their respective CQI plans. The AWMP became a unifying process for Liberty’s very diverse healthcare programs, which might otherwise appear to have little in common. The annual exercise of the AWMP survey was a tangible expression of the company’s commitment to its employees and the principles of CQI. For the first time, program directors and staff were engaged in active discussions of quality and were creating short-term and annual plans for improvement— at the local program level, at the divisional level and at the corporate level.

AWMP identified key areas for company-wide targeted improvements: Liberty’s top corporate leadership reviewed the initial results of the 40 AWMP survey items representing the Baldrige Program’s 7 critical aspects of management with open curiosity. Some results were surprising and some expected. The leadership team engaged in long discussions about both positive and negative results to understand what it said about the company and to identify areas that were most important for improvement. Twelve items that were most aligned with Liberty’s mission and goals were targeted. For example, the survey results showed that too few employees were familiar with the company’s mission and values statements, which had been created the previous year. The leadership team decided it was important to first fully educate its employees about Liberty’s mission and values (items 1a and 1b) before focusing on strategic planning. Similarly, it determined that employee perceptions of the company’s ethical standards (item 7g), excellence of its work products (item 7b) and customer satisfaction (item 7a) needed to improve to reflect Liberty’s most prized commitments. Each year thereafter, the corporate executive team would review the results and the targeted items. To the degree possible, they would devise plans of improvement, such as implementing a Corporate Compliance Program, attaining company-wide Joint Commission certification in HCSS, delivering customer service training, streamlining business procedures, and adding an employee training allowance. Of the original twelve targets, Liberty narrowed its focus to five key areas and achieved major improvement in each as described.

Changes were negligible or slightly negative for the remaining seven items. Speculation about why some areas improved and others did not, or why some sites improved in certain areas and others did not, could fill a book, but it appears that the company-wide clarity and emphasis on mission, values, ethical standards, and customer satisfaction permeated attitudes and actions at every level of the company. AWMP identified key areas for local program improvements:

The vice presidents from the corporate team were also charged with disseminating the results to the program site directors and encouraging them to identify and address items or areas for improvement at the local program level in addition to, or concomitant with, the corporate wide targets. Most of the local programs openly shared their respective survey results with their own employees to invite feedback and discussion about improvements.

These meetings led to a great variety of local QI initiatives that are too numerous and variable to describe, but included the following examples: One large facility program introduced root cause analysis to understand differences in employee satisfaction between its clinical and direct care personnel. Another clinical program introduced an annual training retreat and regular meetings of its clinical staff to improve morale and effectiveness. One 24-hour residential program created cross-shift staff meetings to improve communication across shifts. Two on-site occupational health clinics began newsletters to improve customer awareness of wellness and preventive care opportunities. Another program introduced patient satisfaction surveys to see if increases in their employees perception of customer satisfaction were supported by increased patient satisfaction.

AWMP enabled comparison of performance within the company and to best practices: The annual results of the AWMP promoted data-driven management at the national corporate level and local program level.

Liberty’s corporate leadership could use the Baldrige Criteria for Performance Excellence to evaluate the performance of the company compared to that of extremely successful MBNQA recipient companies. Corporate leadership could asses overall company performance improvement in multiple areas of operation over time. They could assess performance of individual programs and program directors relative to their three respective business divisions and to the company as a whole. They could assess the performance of each of the three business divisions relative to each other and to the whole company. The corporate leadership could select and prioritize targets for improvement and then monitor how individual programs and business divisions were progressing toward those goals.

At the same time, the annual AWMP survey was tremendously valuable to the local, individual program directors. Even program directors with as few as 10 staff could see how their program was performing relative to the rest of the company and to the “best practices” benchmarks of MBNQA recipients. The local program directors could compare their performance results with that of the most similar programs in their respective business divisions. They could monitor performance improvement within their own programs from year to year and evaluate the effectiveness of new quality initiatives or program changes being made at the local program site.

AWMP facilitated candid feedback and business objectivity: The anonymity of the AWMP questionnaire allowed clinicians, managers, and staff at all levels of the organization to express frank, uncensored perceptions of Liberty. It became clear throughout the years of the study, that self-analysis can be a very humbling experience, especially when the company is comparing itself to a standard as high as that achieved by MBNQA recipients. For example, Liberty had always prided itself on having the highest standards and ethics. Therefore, it was painful to discover in 2002 that only 73% of the employees shared this belief about the company. This surprising feedback led to open and frank discussions and the development of action steps to improve and strengthen this important company value. In particular, Liberty implemented a rigorous Corporate Compliance Program in which employees at any worksite could report complaints, illegal activity, and/or unethical conduct with total anonymity on a 24/7 basis.

At the same time, the AWMP methodology provided a valuable way of depersonalizing the results of the survey so that corporate and local program leaders could safely discuss negative results in a more objective, business-like fashion. It will be remembered that the AWMP questionnaire invited staff to give open feedback on any aspect of the company. Given the candidness of these heartfelt expressions, especially in the first 2 years, it could sometimes be difficult for individual program directors to consider negative feedback with equanimity. But the experience of sharing annual results among program directors actually fostered supportive peer bonds that helped managers respond with business objectivity rather than emotion. Instead of engaging in defensive reactions to discount or “explain away” undesirable findings, leaders focused on what could be done to improve their programs. This often would entail open discussions with the highest performing program directors to better understand how they were achieving superior results.

Engagement in monitoring the success of action steps and refining unsuccessful action steps Vol. 35 No. 4 July/August 2013 15 helped corporate and local directors to turn around negative perceptions and improve positive outcomes. In short, the annual survey process became the embodiment of Liberty’s commitment to continuous quality improvement as it strived to achieve results as good as those exemplary companies that have received the MBNQA. Ultimately, Liberty decided against pursuing the MBNQA because, at that time, it was not as well recognized in public sector healthcare. But the experience of using the AWMP survey (and familiarity with the Baldrige Criteria for Performance Excellence embedded within the survey) provided a framework for organizational self-assessment that yielded immense rewards, including the decision, ironically, to obtain company-wide Joint Commission certification rather than the Baldrige Award. In fact, the AWMP study directly facilitated Joint Commission certification because it fulfilled the requirement for a demonstrable process for measuring performance improvement across the corporation. Indeed, in 2011, this same Baldrige-inspired process was regarded so highly that Liberty Healthcare Corporation was selected to make a National Joint Commission HCSS Certification presentation on framework development for Quality Performance Measurement Systems (Shields, 2011).

Although the AWMP survey is no longer used across the entire corporation, it is still used by some local program sites for measuring employee satisfaction, and the survey remains, of course, in Liberty’s toolbox. Today, 9 years after the study began, the MBNQA has gained popularity and recognition in the healthcare field, especially in acute care. If Liberty’s focus should change in this direction, the possibility of pursing the MBNQA could very well become a future goal of excellence.]